Getting from Reno to Sacramento, over the Sierra Nevada, has always been hard. It’s considerably easier now, easier than it’s ever been. But the earliest travelers over the path faced huge hardships. Donner Pass is named for one of the most famous pioneer parties in American history, and the reason they’re famous is because of their failures in getting over the pass safely in the 1840s. 20 years later a wagon road and rail line was carved through the mountains, making the trip considerably easier, but still a grueling journey. With the rise of the personal automobile another 30 years after that, people started looking for ways to get those machines over the mountains too. A natural route to follow was the old wagon road, which had fallen into disrepair. These early road trips were scarcely any easier than what their predecessors had gone through. Rough roads, mechanical breakdowns, and having to pull yourself out of ditches were common obstacles that these early drivers had to deal with. Around 1909 the State government decided to fix up the old wagon road over Donner Summit and bring it up to “modern” road standards. And in 1912 a project was started to build and improve roads across the country, to make coast-to-coast travel by auto possible. The state highway over Donner Summit became part of this Lincoln Highway Project. After these improvements were done, driving to Sacramento was suddenly much easier. But still not without its issues.

This photo from the 1910s shows what those early motorists were up against. This shows the part of the Lincoln Highway that was the steepest climb up to the summit. It looks like this car is headed down the hill, but eagle-eyed historians have noted that the driver seems to be looking back over his shoulder. That would suggest that he’s actually backing up the hill. This was recommended in some early cars because fuel couldn’t get to the engine if the uphill slope was too steep, and also the reverse gear was often lower than first and therefore better for climbing steep hills.

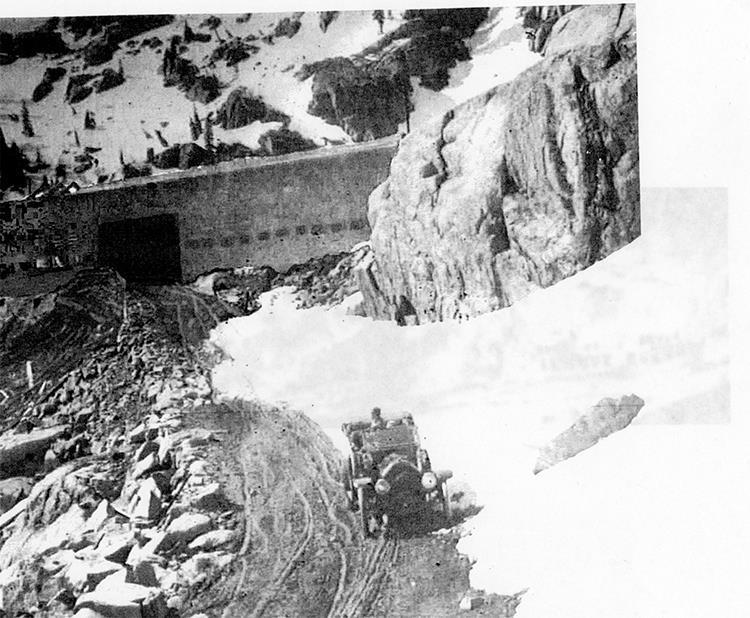

But the biggest obstacle on this part of the road is seen at the top of the hill. The huge structure you see is the wooden snowshed for the Southern Pacific (formerly Central Pacific) Railroad. This was the route of the first Transcontinental Railroad, which had linked the East and the West by rail over 40 years before this photo was taken. The railroad was still going strong at this point, and was still the most popular way to cross the mountains. But the sheer amount of snow that falls on top of Donner Summit had led to them enclosing miles and miles of the tracks inside protective snowsheds. This way, the amount of track that needed to be plowed was minimized. There could be a dozen or more feet of snow falling at the summit, but the train tracks were safe and dry inside their wooden tunnels.

This snowshed created a problem for automobile drivers, though. You can see a gaping hole in the side of the shed; this is where the road crossed the tracks — inside the snowshed. Often the doors were meant to stay closed as well, to keep weather and animals out of the snowshed. So negotiating this rail crossing meant getting out of your car, opening the doors on both sides, looking and listening inside the snowshed to make sure that no trains were coming, then getting back in your car to drive across the tracks. Once on the other side of the tracks you had to get out and close both the doors again. Not the kind of rigmarole you’d want to go through often. But maybe a welcome break after the harrowing drive you’d gone through just getting here.

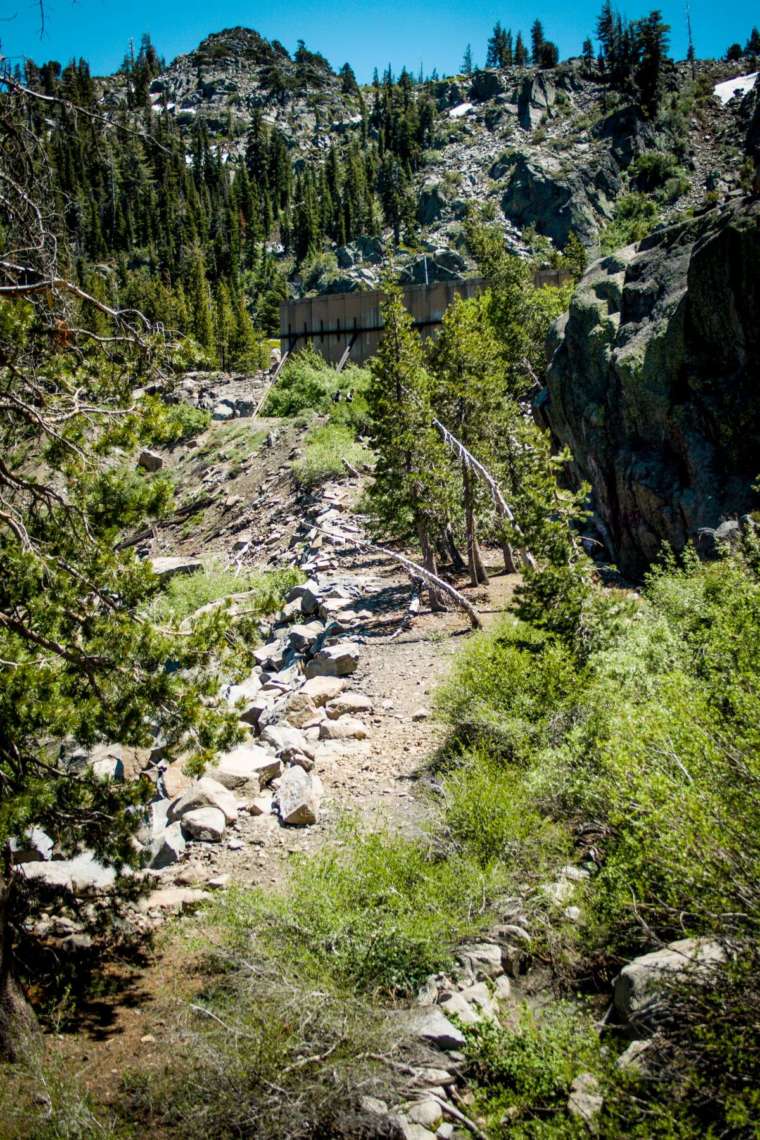

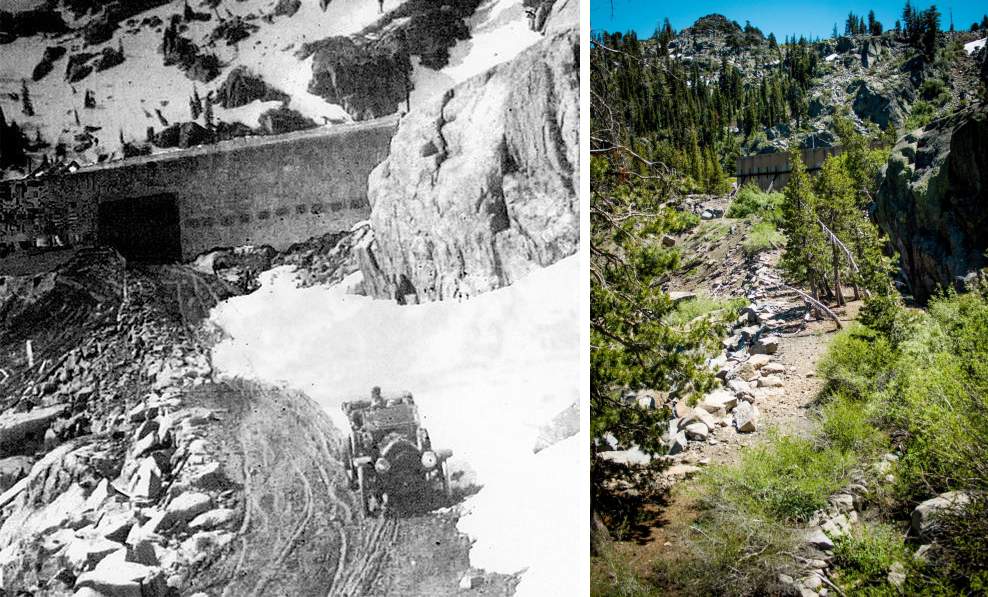

Even back then people knew this was a bad idea. Supposedly there were several accidents inside the tunnel, plus it was just a pain and a burden on the drivers. So this stretch of road didn’t last long. By 1914, the road had been reconfigured slightly at the summit. They came up with a new route that bypassed this tunnel crossing, and instead used an underpass so the autos could pass safely beneath the train tracks with no chance of collision. We’ll take a look at that route in the next post. But this old route has been forgotten and neglected over the past 105 years. If you know where to look, though, you can still see the remnants of the road. It is overgrown with brush and trees, but the boulders that lined the sides of the road are still there, and the roadway itself is still fairly flat. In the background you can still see the snowsheds, but a lot of changes have happened up there too. In the mid 20th century the wooden snowsheds were replaced by concrete. They were also reduced in length, due to improvements in plow technology. This new snowshed is only a partial one, and it lacks the door on the side since there was no more road running through here. But then in 1993 the Southern Pacific decided to abandon these tracks entirely, in favor of a longer tunnel nearby. So now the old road and the old train track both sit unused. A spot that was once the hotbed of travelling between the East and the West is now being reclaimed by nature and hikers.

Bonus Photos

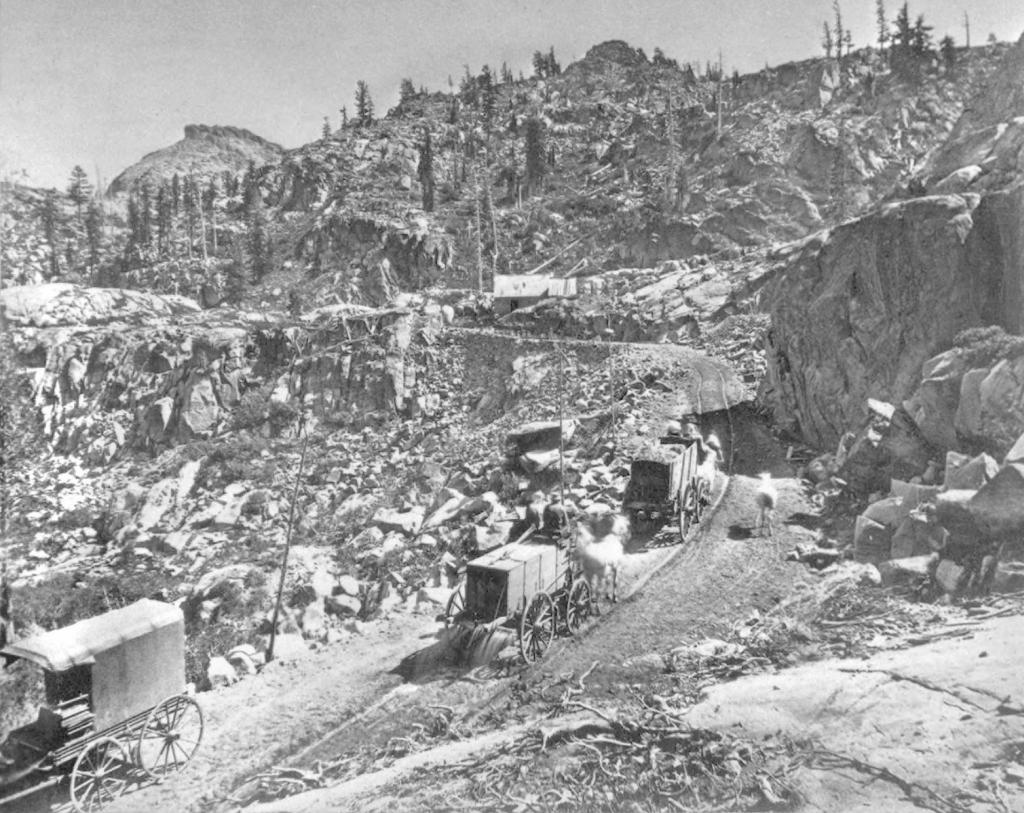

This 1860s photo shows the old wagon road at the same spot. At the top of the hill is construction on the train tracks, which were still unfinished at this time.

Further up the hill, next to the new concrete snowsheds, the old road has been buried underneath debris. This seems to be remnants of the old wooden snowsheds, and boulders that probably were deposited here during tunnel improvements and construction of the concrete snowsheds.

Move on to Part 2 where we look at the newer road that replaced this one, as well as the snowsheds themselves.

Great article, Scott. I have some from up there I would like to reshoot too. Also, many for Virginia City. Maybe we could get together on it.