In Part 1 and Part 2 of this series, we talked about the Southern Pacific Railroad snowsheds at Donner Summit. But only in a roundabout way, since the real focus of those articles was the highways that crisscrossed the tracks at the summit. But now it’s time to look at the snowsheds themselves.

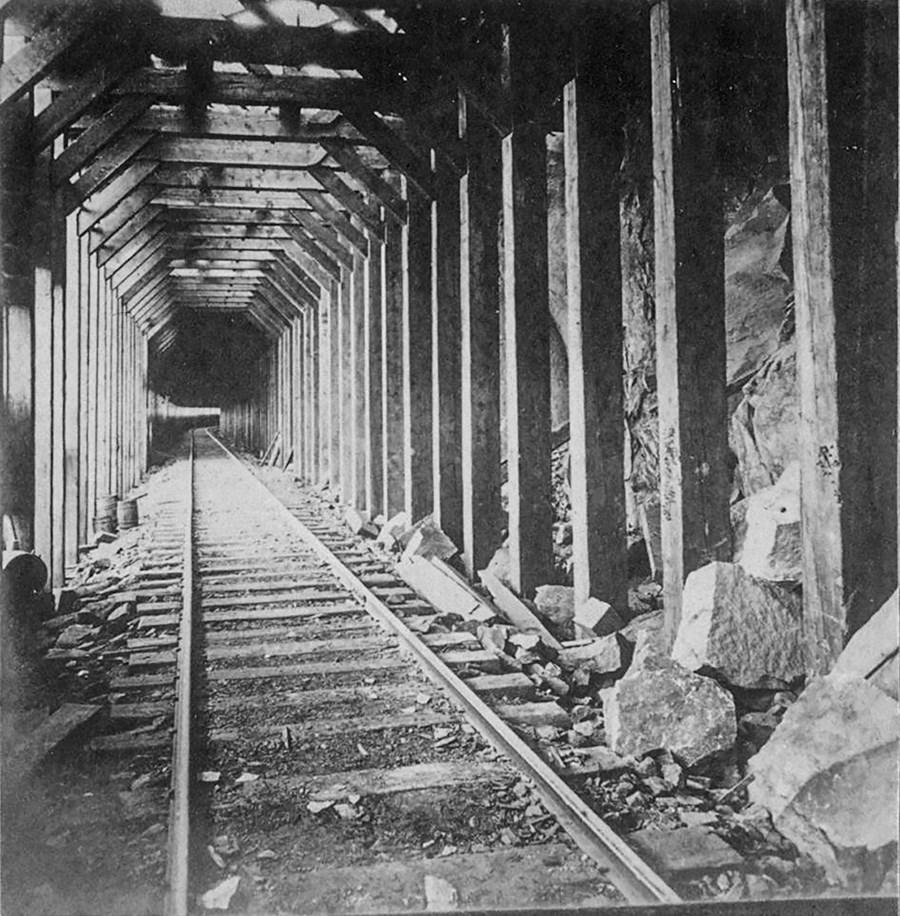

Donner Summit gets a lot of snow. This past winter there was a total of almost 500 inches that fell at the summit. In the past, snowfalls would be even more than that. And while not all of that fell at once (the snow would be 40 feet deep if it did!), you can still get several feet of snow accumulating at any given time. When the railroad came over this summit in the 1860s, snow was one of the major obstacles. With that much snow, they would have to spend more time plowing the tracks than they would hauling freight and passengers. So the decision was made to enclose most of the track over the summit in tunnels. Some of the tunnels were pure rock, burrowing through mountains to create a straight path over the bumpy terrain. But most of the tunnels had to be built out of wood. Long stretches of snowshed, some of them miles long, were built to keep the railroad track and the trains clear of snow. The tunnels were dark, they were smoky because they would hold in the exhaust from the steam engines that passed through, they were prone to catching fire from stray sparks, but they made travel over the mountains a whole lot easier than it would have been without snowsheds.

At some point in the mid 1900s, the wooden snowsheds were torn down and replaced with concrete. This massive undertaking made maintenance of the tunnels easier; no longer would they have to worry about rot or fire risk. Curiously, there were a few stretches, including a bit of space right at the summit, where they did not replace the wooden snowsheds and instead left the tracks to the open air. I’m not sure why they did this, especially since I would think the heaviest snow would be right at the summit.

But by this time they had also taken advantage of more advanced technology to drill an even longer tunnel through the solid rock. This new tunnel was 10,000 feet long, and it created a second track that would bypass all of these snowsheds and the summit itself, staying away from the worst weather. For many years, both of these tracks were in operation at the same time. Most trains would take the new route through the tunnel, but if there was heavy two-way traffic, some of them would be routed over the old route through the snowsheds. Eventually, though, they decided that maintenance even on the concrete snowsheds was becoming burdensome. So in 1993 the Southern Pacific Railroad decided to start using the new tunnel under the summit exclusively, and pulled up the rails on the old historic route and the snowsheds. For the last 26 years, the snowsheds have remained abandoned, given over to hikers and graffiti artists.

Bonus Photos

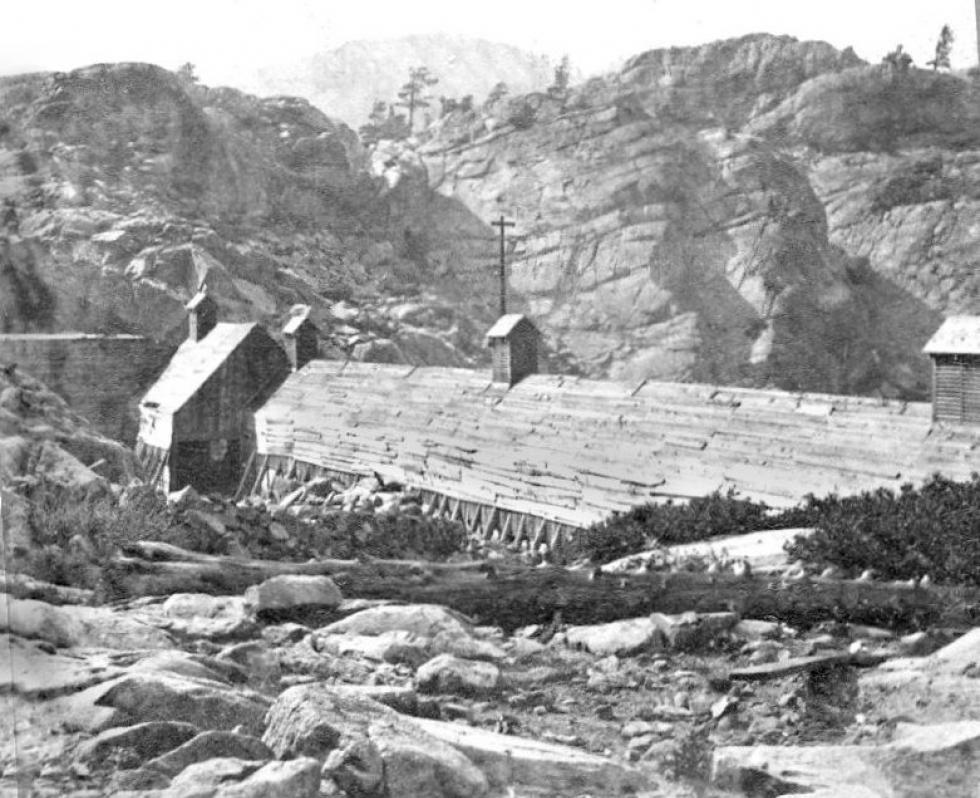

The entire Central Pacific Railroad from Sacramento to Reno was a huge achievement back in the 1860s, one of the most challenging mountain railroads that had been built at the time. But the snowsheds in particular were a favorite subject of photographers of the day, because their impressive size and visuals could be captured in a photograph, even when the other engineering marvels of the railroad couldn’t. These early views of the inside and outside of the snowsheds were produced for an audience that rarely left the cities to see such wonders.

This photo also shows the opening where the wagon road would enter the snowshed

to cross the tracks at the summit, as was talked about in Part 1.